ON THIS DAY in 1911, a team of explorers led by Norwegian Roald Amundsen became the first to reach the South Pole. Amundsen’s expedition was documented in THE LAST PLACE ON EARTH, a 1985 made-for-TV series.

ON THIS DAY in 1911, a team of explorers led by Norwegian Roald Amundsen became the first to reach the South Pole. Amundsen’s expedition was documented in THE LAST PLACE ON EARTH, a 1985 made-for-TV series.

THE STORY OF FILM: AN ODYSSEY (2011) is indeed a journey. Clocking in at 900 minutes (via 15 one-hour segments), it’s a labor of love by both the filmmaker and the audience — and very well worth the ride, for both the cinephile and the fan-on-the-street. (I’m a fan-on-the-street type, by the way.)

THE STORY OF FILM: AN ODYSSEY (2011) is indeed a journey. Clocking in at 900 minutes (via 15 one-hour segments), it’s a labor of love by both the filmmaker and the audience — and very well worth the ride, for both the cinephile and the fan-on-the-street. (I’m a fan-on-the-street type, by the way.)

Like any memorable road trip, STORY is as much about the route and destination as it is about the roadside attractions and unplanned side trips and conversations — all of which leave the traveler with a satisfying and enriching experience.

Based on the 2004 book by film critic and historian Mark Cousins, the award-winning STORY OF FILM explores the never-ending evolution of cinema through an intensive compilation of clips from more than 500 films, along with insightful interviews and commentary. The pace of the film is relentless, sometimes leaving one reeling, but in retrospect, that’s part of the fun of the ride.

In this varied and complex story, Cousins focuses on the driving force in the evolution of film: innovation. Whether innovation comes from artistic vision, technological advances, political and cultural shifts, or cross-pollination of ideas, the fuel that propels the STORY OF FILM forward is constant innovation. And what a story it is.

Just in time for holiday shopping and hunkering down during these cold days of winter, STORY is now available everywhere, online and on DVD. For complete information and to request a screening near you, go to Music Box Films or Hopscotch Films.

A terrific addendum to the documentary is the complete list of film clips that Wikipedia has compiled, which includes links — a brilliant resource for building your must-watch list.

I watched THE STORY OF FILM during a series of screenings on seven consecutive Saturdays at Chicago’s Music Box Theatre. It was just like being in a film class only without the fear of a final exam. The downside was not having a discussion group afterwards. I would love to have had the opportunity to discuss and debate the content before or after each screening, something that theaters that show STORY could do. [One thing I would share is the little thrill I had (blatant self-promotion alert!) when one of the films highlighted was Peter Greenaway’s A ZED & TWO NOUGHTS, which is the movie that leads the protagonists to love in my novel HUMAN SLICES .)

If you end up arranging a multi-day screening of STORY for your family and friends at home, what a great opportunity you would have for such conversations. Get out the wine and start talking.

As I was watching THE STORY OF FILM, I published a series of blog posts about the experience. Here is a recap of those posts, some slightly edited.

IN THE BEGINNING…..

During the first two hours of THE STORY OF FILM: AN ODYSSEY, I learned that the first real movie star, Florence Lawrence, committed suicide with ant poison, that the first close up in cinema featured a sick kitty, and there was some hot erotic dancing going on in the silent movies.

Of course, the history of cinema is comprised of much more than the stuff of cocktail conversations. It’s a vast collection of stories that have impacted each and every one of our lives.

THE STORY OF FILM is quietly narrated by its creator, film critic and historian Mark Cousins. The first two segments, “The Birth of the Cinema (1900 – 1920)” and “The Hollywood Dream (1920s),” provide a sequence of mini tales featuring the inventors, the stars, the breakthroughs, and the innovations that started it all, from the Lumieres to Lloyd. The segments on the evolution of film editing are particularly strong and interesting to me.

Like a professor, Cousins will periodically veer into non-essential territory (like fretting over the glamour and the glossy veneer of Hollywood), which doesn’t particularly add to the narrative, but no matter. He has compiled an anthology of information and resources that will be turned to again and again.

Of course, because of the sheer breadth of material, Cousins must alight on some topics for only moments of time, leaving us wanting more. After seeing the shocking clip of Asta Nielsen’s erotic dance from the 1910 silent film THE ABYSS, for example, I am hoping that someone has created a documentary on THE HISTORY OF EROTIC DANCE IN SILENT FILMS.

(You can view the entire film at http://archive.org/details/Afgrunden_1910. The dance begins at 20:11 and there’s much more to it than in the clip above.)

THE ’20s GET SURREAL AND THE ’30s GET SOUND

In a cab the other day, I glanced at the odd image that appeared on the small television screen mounted on the back of the front seat. “What in the world is that?” I wondered as I looked at the closeup of some beige and bumpy blob. Was it a meteor? an enlarged fat cell? a mutant virus?

The mystery began to unravel as each of the ensuing shots zoomed out to reveal more and more information. As the camera moved back, I saw that the blob was one of many oyster shells chilling on ice. Then a hand holding a knife appeared; the hand belonged to a man who picked up the oyster and pried it open. It turned out that the man was casually sitting at a bar, the atmosphere dark and woody. The big conclusion at the last cut: A restaurant logo and operating hours flashed on the screen.

In the first episodes of THE STORY OF FILM, filmmaker Mark Cousins reminded us how Hitchcock created tension through his “brilliant use of closeups” to start a scene and would then zoom out to reveal place, rather than relying on the traditional establishing shot and moving to closeups from there.

“The guy who directed that restaurant commercial was a Hitchcock fan,” I thought to myself.

The segments of STORY entitled “Expressionism, Impressionism and Surrealism: Golden Age of World Cinema” and “The Arrival of Sound” feature a collection of insights, observations, and trivia, Cousins narrates the series in his lulling, quiet voice, as if he is imparting special secrets, chock full of analysis and comparison/contrast with a big dose of hyperbole.

He says that the the 1920s were “the greatest era in film”; that Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu was “perhaps the greatest film director that ever lived”; and that Alfred Hitchcock was “the greatest image maker of the 20th century.” I couldn’t quite keep up with all of the testimonials to greatness he brings to his commentary, but I have to admit that I enjoy those kinds of big, dramatic statements in his narrative, including pronouncements along the lines of “Cinema can be broken into two periods, before LA ROUE (1923) by Gance and after LA ROUE.” I’m going to use that line all of the time!

Nonetheless, Cousins does provide illustrations to support his declarations, doling out a relentless — and fascinating — selection of clips from more than 40 films include Dreyer’s THE PASSION OF JOAN OF ARC (1928), Murnau’s SUNRISE (1927), Buneul’s UN CHIEN ANDALOU (1929), and Disney’s SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS (1937), just to name a few.

Each selection illustrates the innovations in story, action, and technique that dramatically widened the possibilities in filmmaking during “the golden age of world cinema,” and how this world of visual innovation abruptly changed when sound came into the picture. From the dadaists to the realists, we go bouncing around from innovation to innovation like the crazy journey of the baby carriage in BATTLESHIP POTEMKIN (1925) to the great musical journey of the song “Isn’t It Romantic” from Mamoulian’s LOVE ME TONIGHT (1930).

I am especially intrigued by the movie trivia that Cousins peppers in between his cinema history lessons: That there were 36,000 extras in METROPOLIS. That silent films in France were referred to as “deaf cinema.” That 90 percent of Japanese silent films have been destroyed. That Howard Hawks was responsible for bringing intense speed to cinema (recall the overlapping dialogue in BRINGING UP BABY). That the tragic demise of forgotten Chinese movie star Ruan Lingyu created a national mourning event of historic proportions. That the memorable camera angles in L’ATALANTE were a result of director Jean Vigo not wanting to show the newly fallen snow on the ground. That director Abel Gance watched the restoration of his NAPOLEAN at the 1979 Telluride Film Festival from the window in his hotel room. So many movies, so many footnotes….

As we follow Cousins’ journey through the movie business of the 1930s, he tells us that this era gave rise to the “great genres” of musicals, westerns, horror, gangster films, and comedies. And, at the conclusion of Part 2, Cousins asserts that three key films of 1939 — GONE WITH THE WIND, NINOTCHKA, and THE WIZARD OF OZ —bring “the end of escapism in films.” This statement still stumps me. I wish there had been more exploration of it.

The world is heading to war, and won’t there be plenty of escapist films during the tumultuous times ahead? But for some reason, we won’t get Cousins’ perspective on the films of the war years. The next episode of the series begins with a segment entitled “Post-War Cinema.”

AFTER THE WAR: RUBBLE, SEX & WEEPING

Like life, film never stops changing.

With STAGECOACH (1939), John Ford introduced a new cinematic vision using deep staging and deep focus “that allowed the audience to choose where to look” on the screen.

This innovation, according to Mark Cousins, creator of THE STORY OF FILM: AN ODYSSEY, changed film forever, influencing Orson Welles to take “deep staging as far as it could go” in creating his masterpiece, CITIZEN KANE (1941). Film had never looked like this before.

In the opening of the segment “Post-War Cinema” we see a quick newsreel clip of Hitler and Mussolini sharing a lighter moment. The voiceover provided by Cousins recognizes that these two men wreaked havoc on the world, and then just like that, we’re off. Maybe film of the war years is a separate story for another time.

Nonetheless, the saga of THE STORY OF FILM is a compelling commentary on the constant evolution of film, a reflection of the ever-changing human experience. There has been war. Barriers are going up. Some barriers are coming down.

After the war, the Italian cinema made an indelible mark on filmmaking, with its “rubble” films, presenting the stark, bleak reality of post-war destruction, changing the nature of beauty in cinema, from soft focus romance to dark and dreary reality. The Italian neo-realists, per Cousins, created “cinema that features the boring bits of life,” as opposed to Hitchcock who said that “cinema is life but without the boring bits.”

The convergence of new directorial styles and gloomy world views gave us a Hollywood that began emphasizing film noir, with films like SCARLET STREET (1945) by Fritz Lang; GUN CRAZY (1950) by Joseph Lewis; THE HITCH-HIKER (1953) by Ida Lupino, Hollywood’s only female film noir director; and the pitch-perfect noir classic, THE THIRD MAN (1949) by Carol Reed.

As much as noir became the Hollywood norm during this post-war period, the American film industry still created vibrant stunners such as SINGING IN THE RAIN (1952) and AN AMERICAN IN PARIS (1951), ensuring audiences that joy could still be found in this neo-realist world.

And while the brooding vision of the post-war years went on, borders were redrawn and decolonialization was happening. As a result, the faces of world cinema came to the forefront in Egypt, India, China, Mexico, Britain, and Japan. In the 1950s, the human story went global, and in the film world, the emphasis moved to grand melodramas about the perils of life, love, lust, and survival.

David Lean delivered big drama with GREAT EXPECTATIONS (1946). And American movies certainly had their own glossy tortured tales like Nicholas Ray’s REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE (1955) and JOHNNY GUITAR (1954). The world saw other groundbreaking weepers, such as PATHER PANCHALI (1955) by Satyajit Ray and DONA BARBARA (1943) by Fernando Fuentes and Miguel Delgado.

As with each segment of THE STORY OF FILM: AN ODYSSEY, my list of must-see films expands. I’m starting with CAIRO STATION (1958), with Youssel Chahine, which Cousins taga as “the first great African/Middle Eastern film,” and a revisit to the ultimate sexy melodrama of the 1950s, …AND GOD CREATED WOMAN (1956) by Roger Vadim and starring Brigitte Bardot.

THE PROFOUNDLY PERSONAL FILM ARRIVES

After the plethora of sweeping, epic melodramas in post-WWII films, the next era of innovation in moviemaking took the opposite road: exploring the “profoundly personal” experience found in the New Wave cinema of the 1950s and ’60s.

During the beginning of this era in film history, Cousins cites four great directors as the movers and shakers who took film to this new, personal level: Ingmar Bergman, Robert Bresson, Jacques Tati, and Frederico Fellini. These innovators championed the role of film itself becoming an integral part of the narrative.

Citing Bergman’s SUMMER WITH MONIKA (1953), for example, there is a groundbreaking scene where Monika looks at us directly, straight into the camera, changing the audience’s relationship to the story being exposed on the screen. In Robert Bresson’s masterpiece, THE PICKPOCKET (1959), Cousins notes that the film demonstrates the “total rejection of gloss,” stripping down the story to emphasize the flatness of the everyday. Thirdly, he recognizes the briliance of visionary director Tati with MONSIEUR HULOT’S HOLIDAY (1953), a film which basically affirms that “the story doesn’t exist,” Tati preferring incidence and details to a plot line. And last but not least, Cousins highlights the work of Frederico Fellini, whose major construct was portraying life as a circus world, with films such as NIGHTS OF CABIRIA (1957), using improvisation as opposed to linear storytelling.

As the story of film evolves, these four influential filmmakers gave way to the French New Wave directors of the early sixties. Cousins calls these innovators “the film school generation,” who embraced filmmaking as an intellectual endeavor, creating even more “narrative ambiguity” in movies and focusing on the meaning of life and existentialism.

For starting an exploration of this period, go with classics such as CLEO FROM 9 -5 (1962) by Agnes Varda; LAST YEAR IN MARIENBAD (1961) by Alain Resnais; Francois Truffaut’s 400 BLOWS (1959); Jean Luc Goddard’s A MARRIED WOMAN (1964); Marco Ferreri’s THE WHEELCHAIR (1960); Sergio Leone’s FISTFUL OF DOLLARS (1964); and I AM CURIOUS YELLOW (1967) by Filgot Sjoman.

And then like every other era, the French New Wave lost its steam and made way for a new world cinema that “dazzled” the industry.

_____________________

Part of the experience of watching this STORY OF FILM series is sinking down into your seat and giving into the filmmaker’s hypnotic narration. Have a listen….

EUROPE’S NEW WAVE RIPPLES AROUND THE WORLD

Ten hours into THE STORY OF FILM: AN ODYSSEY , my head was reeling with “begats,” such as this-scene-was-influenced-by-this-scene-which-was-influenced-by-this-scene etc., etc. In sum, like all art — and life itself — filmmaking is influenced by what has come before, the impact of cultural and political changes, and what technology allows.

As this history of film gathers steam across time, the cross-pollination of influences and innovation gets more and more diverse and less linear. In the segments of THE STORY OF FILM that explore movies of the 1960s and 1970s, filmmaker and historian Mark Cousins examines the influential directors of Europe’s New Wave, the emergence of a new, “dazzling” world cinema, and the evolution of American film post-Hollywood’s Golden Age. As this new wave of world cinema grows and matures, filmmaking around the world doesn’t just reflect culture, it attempts to change it.

Here are only just a very few of the notable films cited by Cousins from the world cinema directors of the 1960s and 1970s to add to your Watch List:

-Roman Polanski’s TWO MEN AND A WARDROBE (1958) and THE FEARLESS VAMPIRE KILLERS (1967)

-Andrei Tarkovsky’s ANDRE RUBLEV (1966)

-Milos Forman’s THE FIREMAN’S BALL (1967)

-Nagisa Oshima’s BOY (1969)

-Vera Chytilova’s DAISIES (1966)

-Ousmane Sembene’s BLACK GIRL (1969)

-Ritwik Ghatak’s THE CLOUD-CAPPED STAR (1960)

-Werner Fassbinder’s THE BITTER TEARS OF PETRA VAN KANT (1972)

-Donald Cammell & Nicholas Roeg’s PERFORMANCE (1970)

-Bernardo Bertolucci’s THE CONFORMIST (1970)

One of the most spellbinding moments in THE STORY OF FILM is watching the beautiful and imaginative continuous shot from the funeral scene in I AM CUBA (1964) by Mikhail Kalatozov. What an achievement — without computer-generated graphics. You can watch this one again and again.

Following the growth in world cinema, Cousins opines that American film of the ’70s was next up for a sea change, emphasizing the cynical and dissident films, such as Mike Nichols’ THE GRADUATE (1967) and CATCH 22 (1970); the “assimilationist” film, like Peter Bogdanovich’s THE LAST PICTURE SHOW (1971), which simultaneously pays homage to film’s past and its future; and identity films, such as Martin Scorsese’e ITALIANAMERICAN (1974).

The next era covered in THE STORY OF FILM “ushers in the age of the multiplex,” with blockbusters like JAWS, STAR WARS, and THE EXORCIST from the States, and Bollywood and Bruce Lee from Asia. Stay tuned….just a few more hours to go!

THE THRILLS OF THE ’70s & THE POWER OF THE ’80s

When I think of the blockbusters of the 1970s, I think of Spielberg gems like JAWS (1975) and CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND (1977); Freidkin’s THE EXORCIST (1973); and Lucas’s STAR WARS (1977) masterpiece.

According to Mark Cousins, narrator and filmmaker of THE STORY OF FILM: AN ODYSSEY, these innovative films were the candy that lured American audiences back into the country’s movie theaters, these new things being built that were called “multiplexes.”

These Hollywood blockbusters were innovative, to be sure, because of new technology like Dolby sound and enhanced deep space perspective. But there was something more in these movies, a focus on universal emotions, showcasing REALLY BIG, inspired moments that relied on the ever-present “awe and revelation scene,” where the audience doesn’t see what the actor sees. Picture CLOSE ENCOUNTERS, with Richard Dreyfuss and Melinda Dillon, staring, dumfounded, while we wait in expectation to see what they’re seeing, spellbound ourselves, mouths open, on the edge of our seats.

And while American audiences were wowed by their newest contemporary directors, the Asian mainstream cinema was also being kickstarted (pun intended) by the Shaw Brothers Studios (Hong Kong’s sprawling film center) and Bruce Lee movies. From Lee’s physicality, the martial arts genre grew, inspiring more cinematic innovation, with the super fast cut and slow motion “spinning” effects that enthrall and mesmerize and later show up in films like THE MATRIX (1999).

The Bollywood film industry also became a force in this era, building the biggest moviemaking empire in the world, churning out 433 movies in one year, for example, and in the present day releasing more than 1,000 per year, double that of a typical production year in Hollywood.

Since almost everyone in the world has seen them, you may want to add two world cinema blockbusters from the ’70s on your must-watch list: THE MESSAGE: THE STORY OF ISLAM (1976), directed by Moustapha Akkad and starring Anthony Quinn, which Cousins says has probably been “seen by more people than any other,” and SHOLAY (1975) by director Ramesh Sippy, considered “one of the most influential films of the time.” It played in one cinema alone for 7 years!

As the 1970s retreated and the ’80s emerged, film took a new turn, where the focus of moviemaking was on politics, leveraging film as a protest mechanism heard ’round the world. Cousins cites a long list of influential titles from the “fight the power” era: THE HORSE THIEF (1988) from China, which led the rebirth of that country’s film industry; REPETANCE (1984) by Tengiz Abuladze; COME AND SEE (1985), pegged by Cousins as the “greatest war film ever made”; Krzysztof Kieslowski’s A SHORT FILM ABOUT KILLING (1988), which changed death penalty law in Poland; and award-winning MY BEAUTIFUL LAUNDRETTE (1985), which Cousins calls “a kick in the balls to right-wing England.”

Cousins defines these ’80s protest films as cinema that “speaks truth to power,” and as this influence grew around the world, America’s up-and-coming directors like David Lynch, Spike Lee, John Sayles, and David Croenenberg took note.

These heady days of filmmaking of the ’80s made way for stretching the boundaries of world cinema even further as the 1990s arrive.

ARTIFICE & AUTHENTICITY

The last episodes of the 15-part of THE STORY OF FILM: AN ODYSSEY, filmmaker and narrator Mark Cousins continues to explore the constancy of change in cinema as it moves from celluloid to the digital era. Throughout the 1990s and onward, authenticity and artifice weave in and out of the picture as directors all over the world explore, question, and reference the realm of possibilities.

During this time, film becomes more “real” with expanded use of documentary style demonstrated in Iranian films like LIFE, AND NOTHING MORE (1992) by Abbas Kiarostami and the handheld roughness of BLAIR WITCH PROJECT (1999) by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez. Paradoxically, directors are exploring the “unreal” with movies such as the jaw-dropping HOUSE OF FLYING DAGGERS (2004) by Yimou Zhang, horror film RINGU (1998) by Hideo Nakata; and the “mash-up” music video style of MOULIN ROUGE (2001) by Baz Luhrmann.

Of course, as time moves on, computer-generated graphics create spectacle of the kind created in GLADIATOR (2000) and AVATAR (2009) to the point that films start feeling like video games. (The utter disdain with which Cousins spits out the words “hobbits and avatars” is highly entertaining, by the way.)

On the other end of the spectrum are directors like Van Trier, Tarantino, and the Coen Brothers who erase boundaries and artifice to create films that strive to be more real — and less real — at the same time. (I’m no blood-and-guts movie fan, but I do have to say that the commentary on these movies was intriguing food for thought.)

Like the adage goes, “Nothing is constant but change.” And film is no different. Technology will continue to influence the realm of possibilities. More corporate marketing (and perhaps less of culture) will continue to influence what’s seen on the silver screen. And directors of every scale will continue to strive to deliver their individual visions.

One of the most compelling clips in this part of STORY is the side-by-side comparison the shower scene in Hitchcock’s PSYCHO and Van Sant’s 1998 version.

Like an ongoing conversation with the past, film will continue to quote film.

Around the world, film is the medium in which we tell our stories and share the way we see the world. Just a few years ago, the concept of a Home Projectionist was hard to explain. Now, not only are we all program directors in our own homes and mobile devices, but we also all have the technology at hand to be filmmakers.

It’s always good to know where you’ve been before you head out to new horizons. Why not start your trip with THE STORY OF FILM?

Gloria Bowman is a writer, storyteller, blogger, movie lover, freelance editor,

and author of the novel, Human Slices.

Access her blog at www.gloriabowman.com; on Twitter @GloriaBow

If you spent most of your time watching movies this past week, you might have missed these articles here at Home Projectionist:

Visit Home Projectionist on Facebook

FROM THE BEGINNING, it was a performance piece.

FROM THE BEGINNING, it was a performance piece.

A Christmas Carol was published in December 1843. By February 1844, it had three London stage productions. Charles Dickens himself did 127 readings from it.

There are more than 20 movie versions. The Wikipedia article on adaptions left out the one starring Barbie and the 2012 gay version shot in Chicago. Somewhere in this world there is a mime version starring Marcel Marceau.

Dickens was a theatrical, highly visual writer who was unafraid of emotion. Social injustice angered him. All these elements are in the book.

He knew what he had in Christmas Carol, judging by this letter to a friend (where for some reason he refers to himself in the third person):

[He] wept and laughed and wept again, and excited himself in a most extraordinary manner in the composition; and thinking whereof he walked about the black streets of London, fifteen and twenty miles many a night when all the sober folks had gone to bed. . . . Its success is most prodigious.

The first printing sold out in one day.

This movie was rejected for a Christmas run at Radio City Music Hall because it was considered too “adult.” It did poorly in the United States, but was a hit in England. Filmed in black and white, it has a shadowy, otherworldly look.

Fan’s deathbed scene. In book Scrooge makes no promise to look after her son Fred. He is not at his sister’s side when she dies either.

What happens to Scrooge’s former fiancée. In movie she works at a homeless shelter, apparently unmarried. In book she marries happily and has a large family.

Tiny Tim. In movie he is cured of his disability. Dickens just says he does not die.

This clip shows Scrooge’s reconciliation with his nephew Fred:

This movie was a hit in the United States, but did poorly in England.

When Scrooge gives Bob Cratchit a raise, you might wonder why he needs more money. He and his family look well fed and healthy, and their house seems solidly middle class. This infidelity to Dickens both sweetens and weakens the plot. As a poor family, the Cratchits’ goodness is heroic. When they are well off, the story turns toward sentimentality. The difference is major.

But it is a likable movie, with several fine performances. Its endurance as a holiday classic is easy to understand.

Marital status of Scrooge’s nephew Fred. In movie he cannot marry his fiancée without Scrooge’s financial assistance. In book Fred is a married man who asks/needs nothing of Scrooge.

Scrooge’s failed romance with Belle. She is not in the movie.

The children named Ignorance and Want. They no longer cling to the Ghost of of Christmas Present. Like Belle, they have disappeared.

This clip shows the Cratchits’ Christmas dinner:

This movie had a theatrical release in England, but was shown only as a TV movie in the United States. Respectful and mostly faithful, it honors the dark side of the tale as well as the light.

David Warner’s Bob Cratchit feels anger he doesn’t dare express. George C. Scott resists the temptation to overplay the big speeches.

The last scene. Tiny Tim is healed of his lameness. Dickens did not—repeat, DID NOT—ever say Tim was cured.

Scrooge conducting business on Christmas Eve. Scene where he bullies a couple of businessmen into paying a high price for a shipment of corn is a screenwriter’s invention.

The ringing bell that announces Marley’s ghost. Here the filmmakers one-upped Dickens. Dickens doesn’t use that bell to any particular effect. The filmmakers do.

The movie bell is shrouded in cobwebs. It obviously has not rung in years, if ever. Of course not—Scrooge hates people. That unused bell emphasizes his loneliness.

This clip is long—about 10 minutes. At 2:24 is the ringing bell:

The drink Scrooge promises to share with Bob, smoking bishop, is made with port, red wine, sugar, spices, and roasted lemons and oranges. Here is a virtual mug of this hot, boozy drink.

***

If you’ve seen any of the above movies, what do you think of them? What about other adaptations?

Has anybody read the book? Amazon has a free Kindle edition.

Lindsay Edmunds blogs about robots, writing, life in southwestern Pennsylvania, and sometimes books and movies at Writer’s Rest. She is the author of a novel about love in the age of artificial intelligence: Cel & Anna.

ON THIS DAY in 1968, The Rolling Stones, Jethro Tull, The Who, John Lennon and other musicians performed a concert in Wembley, England. A film of the event was released in 1996 as THE ROLLING STONES ROCK AND ROLL CIRCUS.

TCM Remembers for 2012. We lost a lot of great ones…

ON THIS DAY in 1884, Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn was published for the first time, in England and Canada. Twain’s novel was adapted for the screen in 1939 as HUCKLEBERRY FINN, and starred Mickey Rooney.

ON THIS DAY in 1905, screenwriter and member of “the Hollywood Ten” Dalton Trumbo was born. His refusal to testify about Communists in the film industry was depicted in the 2007 documentary, TRUMBO.

The great screwball comedies of the ‘30s and ‘40s from acclaimed directors like Wyler, Hawks, Lubitsch, and Sturges are always crowd pleasers. These are movies chock full of star power, snappy dialogue, stunning sets, and buckets of style.

What’s not to like?

Sometimes, I fear, what is not to like is when mean-spirited revenge is played for comedy and a supposedly “happy ending” of wedded bliss is sure to be doomed because the bride and groom will, in no way, ever operate on the same level and with any sense of trust.

Call me a poop, but for that reason, I just can’t put THE LADY EVE (1941) by Preston Sturges at the top of my list of favorite comedies from that era.

You’ll get no argument from me that THE LADY EVE is indeed a funny and clever film with laugh-out-loud lines so full of double entendre that they’re actually shocking. I can watch selected scenes from this movie over and over and over and never stop being entertained by their hilarity.

I have a friend who often waxes on how THE LADY EVE is one of the most brilliant comedies of all, and I’m just using this space to put in my two cents that it’s a bit depressing as well.

Barbara Stanwyck is gorgeous as Jean, a manipulative con artist, and Henry Fonda is the handsome but bumbling Charles Pike (aka “Hopsie”) as her love interest — although you can’t help but wonder how the scenes would have sounded and looked with Hepburn and Grant in charge. Co-stars William Demarest as Fonda’s right-hand man is delightful, and Charles Coburn as Stanwyck’s father is the lovable criminal you can’t help but like.

On a trans-Atlantic crossing, Stanwyck plays the ultimate “cruiser,” setting her sights on Fonda when she discovers he is an heir to a beer fortune—and even better, he is completely clueless to feminine and cardsharp wiles. Within minutes of their first meeting, Stanywck gets him to her room and actually has him picking out her shoes and falling on his knees to slip them on for her. Who is this guy?

And who in the world is this dame? She is lusty and lovely and not to be trusted. You feel a bit sorry for Fonda’s Hopsie character, but the again, maybe not.

Hopsie falls hard for her but quickly finds out that Stanwyck’s Jean isn’t who she says she is. Hurt and dismayed, he rejects her. She doesn’t even try to explain that she has genuine feelings for him and regrets trying to dupe him. Couldn’t they just have had an honest conversation to clear things up? There could have been some solid comedy from that scenario. Instead, she turns callous and bitter and plots her revenge. She even calls him a “sucker.”

Once Stanwyck’s countenance goes cold and her wheels start turning on an “I’ll get you” path, the movie loses its laugh power. I’m not rooting for her anymore. I’m annoyed by her nasty spirit and smug self-assuredness that she’s in a fight to win, in the name of winning alone, not in the name of finding love.

If you’re watching THE LADY EVE at home, this is the point in the movie when might want to get up, pour yourself a glass of wine, go to the bathroom, make a list of things to do for the next day. Keep within earshot to catch a few clever lines however.

And when you hear froggy-voiced Eugene Palette (playing Fonda’s father) banging on the table demanding that someone feed him, settle back in. He steals the show. The movie regains its momentum here and as we watch the kitchen staff get ready for a dinner party—a brilliant series of scenes. This is joyful moviemaking at its best. But then the devious Stanwyck walks in, and the spirit of fun dissolves.

A lot of time, and I mean A LOT of time goes by as Stanwyck lies, postures, and poses, and we head to the inevitable conclusion: Hopsie will stay clueless and Stanwyck will get her man. And no one, in the end, will be the happier for it.

Gloria Bowman is a writer, storyteller, blogger, movie lover, freelance editor,

and author of the novel, Human Slices.

Access her blog at www.gloriabowman.com; on Twitter @GloriaBow

For the movie lovers on your gift list, of course, movies are always welcome. (Hint: Who wouldn’t want TCM’s Joan Crawford collection? It’s on sale too.)

Another route to go for the movie lover who has everything is original, affordable movie art from Mondo Gallery, a division of the Alamo Drafthouse movie theater organization.

Mondo creates “limited edition screen printed posters for our favorite classic and contemporary films, in addition to vinyl movie soundtracks, VHS re-issues, and apparel.”

Per a recent WSJ article by Don Steinberg, the gallery “commissions world-class illustrators and graphic artists to create posters for new and vintage films the way you’d do it if art was the only consideration, not market research.” Special note: The article includes a fabulous slide show of the posters for your viewing pleasure.

With an array of artists producing posters, styles vary widely. The best part? These are “collectible artworks that are very affordable ($35 to $100, or so).”

The worst part? They’re hard to get.

Competition is fierce to nab one of these limited editions. The article continues to state, “Savvy film buffs know that if you want to score a Mondo, it’s best to monitor Twitter and Facebook for on-sale alerts…and then click fast.” And if you miss out, “there’s a healthy aftermarket for Mondo posters on eBay.” But prepared to shell out “3 to 10 times their original prices.”

Visit Mondo on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/mondotees or through the Mondo web site at http://www.mondotees.com/.

Happy shopping!

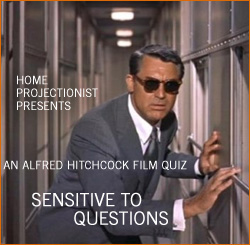

Good evening. We’re seeing a lot of the Master of Suspense these days, what with his self-titled movie currently playing at theaters. But we have always had the opportunity to catch his familiar face and form often over the years, right there during his cameo appearances in the very pictures he directed. We can identify that distinctive shape easily in those movies, but can you name the movie’s title? (In case you missed it last week, here’s part 1.)

Good luck, Mr. Thornhill, wherever you are…

Take the Quiz!(*The quiz title was inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s North By Northwest: “Something wrong with your eyes?” “Yes”, says the sunglass-clad Roger O. Thornhill (Cary Grant), “They’re sensitive to questions”. In the hotel room of the fictitious George Kaplan, Roger spots a photograph of his kidnapper, Philip Vandamm, and says, “Oh, well, look who’s here!”.)

A bucket list blog: exploring happiness, growth, and the world.

this blog will disappear on the day that my heart is alive again

Where classic films stand out above the rest

The Power of Words

Incredible tips for Classrooms and Staffrooms

Watch as I amaze and astound with opinions about what TV shows I like!

Political Co-Dependency Intervention

Tablecloths, Table Toppers, Placemats our specialty

I blog about everything and anything, never hesitate to question....

The works and artistic visions of Ken Knieling.

entertainment & belief go heart to heart

the Story within the Story

Horror With Humour

unparalleled film reviews, news, and top 10s

Mostly movies with a smattering of TV, books, and LEGO thrown in!

MUSINGS : CRITICISM : HISTORY : NEWS

Film, Comics, Music, News, You want it? We've got it!

On This Day....

Celebrate Silent Film

...a classic film and TV blog

Entertainment and Everyday News brought to you in a flash

wendy maruyama, art work, executive order 9066, the tag project

A guy with a desk...

www.attentiallupo2012.com

Improving the English language one letter at a time

Seek first the kingdom of God and his righteousness. (Matthew 6:33)

draws comics

Canadian trivia and history in bite size chunks!

“There are always two people in every picture: the photographer and the viewer.” -Ansel Adams

Independent movie reviews and more...

Stories

The life and times of Erik, Veronica and Thomas

a site for movie lovers' eyes

Short reviews on high quality films. No spoilers.

For the Love of Leading Ladies

A blog for movie enthusiasts and weed lovers

A Blog For Every Movie Lover

knitting and blogging in Italy in times of economic crisis

** OFFICIAL Site of Artist Ray Ferrer **

Not just another WordPress.com site, but an extraordinary place to spend a weekend, grill a cheese sandwich and watch a film to improve your life and stimulate a few of the grey cells.